Date: June 20, 2012

Under Obama - Losing Our Sons

From: Freedom is Knowledge

- Please feel free to share these stories with others. All news links have been verified -

Links to Web sites are highlighted in color

Headline:

What, the Democrat Party didn't know he would try to fundamentally change America? - Webmaster

Look who has approved Attorney General Holder's request to protect Justice System's corrupt Fast and Furious documents under . . . wait for it . . . Executive Privilege.

- See Addendum -

Download video of event and watch in Windows Media - (Note allow about 30 seconds for large file.)

House panel votes 23-17 to place Holder in contempt of Congress

Mother of Murdered Border Patrol Agent Speaks Out on Executive Privilege - June 20, 2012

Holder's Letter of Request for Executive Privilege

Source: FOX News Insider

The President

The White House

Washington, D.C. 20500Dear Mr. President,

I am writing to request that you assert executive privilege with respect to confidential Department of Justice (“Department”) documents that are responsive to the subpoena issued by the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform of the United States House of Representatives (“Committee”) on October 25, 2011. The subpoena relates to the Committee’s investigation into Operation Fast and Furious, a law enforcement operation conducted by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (“ATF”) and the United States Attorney’s Office for the District of Arizona to stem the illegal flow of firearms from the United States to drug cartels in Mexico (“Fast and Furious”). The Committee has scheduled a meeting for June 20, 2012, to vote on a resolution holding me in contempt of Congress for failing to comply with the subpoena.

I.

The Committee’s subpoena broadly sweeps in various groups of documents relating to both the conduct of Operation Fast and Furious and the Department’s response to congressional inquiries about that operation. In recognition of the seriousness ofthe Committee’s concerns about both the inappropriate tactics used in Fast and Furious and the inaccuracies concerning the use of those tactics in the letter that the Department sent to Senator Grassley on February 4, 2011 (“February 4 Letter”), the Department has taken a number of significant steps in response to the Committee’s oversight. First, the Department has instituted various reforms to ensure that it does not repeat these law enforcement and oversight mistakes. Second, at my request the Inspector General is investigating the conduct of Fast and Furious. And third, to the extent consistent with important Executive Branch confidentiality and separation of powers interests affected by the Committee’s investigation into ongoing criminal investigations and prosecutions, as well as applicable disclosure laws, the Department has provided a significant amount of information in an extraordinary effort to accommodate the Committee’s legitimate oversight interests, including testimony, transcribed interviews, briefings and other statements by Department officials, and all of the Department’s internal documents concerning the preparation of the February 4 Letter.

The Committee has made clear that its contempt resolution will be limited to internal Department “documents from after February 4, 2011, related to the Department’s response to Congress.” Letter for Eric H. Holder, Jr., Attorney General, from Darrell E. Issa, Chairman, Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, U.S. House ofRepresentatives at 1-2 (June 13, 2012) (“Chairman’s Letter”). I am asking you to assert executive privilege over these

documents. They were not generated in the course of the conduct of Fast and Furious. Instead, they were created after the investigative tactics at issue in that operation had terminated and in the course of the Department’s deliberative process concerning how to respond to congressional and related media inquiries into that operation.In view of the significant confidentiality and separation of powers concerns raised by the Committee’s demand for internal documents generated in response to the Committee’s investigation, we consider the Department’s accommodations regarding the preparation of the February 4 Letter to have been extraordinary. Despite these accommodations, however, the Committee scheduled a vote on its contempt resolution. At that point, the Department offered an additional accommodation that would fully address the Committee’s remaining questions. The Department offered to provide the Committee with a briefing, based on documents that the Committee could retain, explaining how the Department’s understanding of the facts of Fast and Furious evolved during the post-February 4 period, as well as the process that led to the withdrawal of the February 4 Letter. The Committee, however, has not accepted the Department’s offer and has instead elected to proceed with its contempt vote.

As set forth more fully below, I am very concerned that the compelled production to Congress of internal Executive Branch documents generated in the course of the deliberative process concerning its response to congressional oversight and related media inquiries would have significant, damaging consequences: It would inhibit the candor of such Executive Branch deliberations in the future and significantly impair the Executive Branch’s ability to respond independently and effectively to congressional oversight. This would raise substantial separation of powers concerns and potentially create an imbalance in the relationship between these two co¬ equal branches of the Government. Consequently, as the head of the Department of Justice,

I respectfully request that you assert executive privilege over the identified documents. This letter sets forth the basis for my legal judgment that you may properly do so.II.

Executive privilege is “fundamental to the operation of Government and inextricably rooted in the separation of powers under the Constitution.” United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. 683,708 (1974). It is “a necessary corollary of the executive function vested in the President by Article II of the Constitution.” Congressional Requests for Confidential Executive Branch Information, 13 Op. O.L.C. 153, 154 (1989) (“Congressional Requests Opinion”) (opinion of Assistant Attorney General William P. Barr); see U.S. Const. art. II,§ 1, cl. 1 (“The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.”); U.S. Const. art. II, § 3 (The President shall “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed ….”). Indeed, executive privilege “has been asserted by numerous Presidents from the earliest days of our Nation, and it was explicitly recognized by the Supreme Court in United States v. Nixon.” Congressional Requests Opinion, 13 Op. O.L.C. at 154.

The documents at issue fit squarely within the scope of executive privilege. In connection with prior assertions of executive privilege, two Attorneys General have advised the President that documents of this kind are within the scope of executive privilege. See Letter for the President from Paul D. Clement, Solicitor General and Acting Attorney General, Re: Assertion of Executive Privilege Concerning the Dismissal and Replacement of US. Attorneys at

6 (June 27, 2007) (“US. Attorneys Assertion”) (“[C]ommunications between the Department ofJustice and the White House concerning … possible responses to congressional and media inquiries about the U.S. Attorney resignations … clearly fall within the scope of executive privilege.”); Assertion of Executive Privilege Regarding White House Counsel’s Office Documents, 20 Op. O.L.C. 2, 3 (1996) (“WHCO Documents Assertion”) (opinion of Attorney General Janet Reno) (concluding that”[e]xecutive privilege applies” to “analytical material or other attorney work-product prepared by the White House Counsel’s Office in response to the ongoing investigation by the Committee”).

It is well established that “[t]he doctrine of executive privilege … encompasses Executive Branch deliberative communications.” Letter for the President from Michael B. Mukasey, Attorney General, Re: Assertion of Executive Privilege over Communications Regarding EPA ‘s Ozone Air Quality Standards and California’s Greenhouse Gas Waiver Request at 2 (June 19, 2008) (“EPA Assertion”); see also, e.g, US Attorneys Assertion at 2; Assertion of Executive Privilege with Respect To Clemency Decision, 23 Op. O.L.C. 1, 1-2 (1999) (“Clemency Assertion”) (opinion of Attorney General Janet Reno). The threat of compelled disclosure of confidential Executive Branch deliberative material can discourage robust and candid deliberations, for “[h]uman experience teaches that those who expect public dissemination of their remarks may well temper candor with a concern for appearances and for their own interests to the detriment of the decisionmaking process.” Nixon, 418 U.S. at 705. Thus, Presidents have repeatedly asserted executive privilege to protect confidential Executive Branch deliberative materials from congressional subpoena. See, e.g, EPA Assertion at 2-3; Letter for the President from Michael B. Mukasey, Attorney General, Re: Assertion of Executive Privilege Concerning the Special Counsel ‘s Interviews of the Vice President and Senior White House Staff at 2 (July 15, 2008) (“Special Counsel Assertion”); Letter for the President from John Ashcroft, Attorney General, Re: Assertion of Executive Privilege with Respect to Prosecutorial Documents at 2 (Dec. 10, 2001) (“Prosecutorial Documents Assertion”);

Clemency Assertion, 23 Op. O.L.C. at 1-4; Assertion of Executive Privilege in Response to

a Congressional Subpoena, 5 Op. O.L.C. 27,29-31 (1981) (“1981 Assertion”) (opinion of

Attorney General William French Smith).Because the documents at issue were generated in the course of the deliberative process concerning the Department’s responses to congressional and related media inquiries into Fast and Furious, the need to maintain their confidentiality is heightened. Compelled disclosure of

such material, regardless of whether a given document contains deliberative content, would raise “significant separation of powers concerns,” WHCO Documents Assertion, 20 Op. O.L.C. at 3, by ‘”significantly impair[ing]“‘ the Executive Branch’s ability to respond independently and effectively to matters under congressional review. US. Attorneys Assertion at 6 (“the ability of the Office of the Counsel to the President to assist the President in responding to [congressional and related media] investigations ‘would be significantly impaired’ if a congressional committee could review ‘confidential documents prepared in order to assist the President and his staff in responding to an investigation by the committee seeking the documents”‘) (quoting WHCO Documents Assertion, 20 Op. O.L.C. at 3) (alterations omitted). See generally The Constitutional Separation of Powers Between the President and Congress, 20 Op. O.L.C. 124,126-28, 133-35 (1996) (explaining that, under Supreme Court case law, congressional action that interferes with the functioning of the Executive Branch, including “attempts to dictate the processes of executive deliberation,” can violate general separation of powers principles); Nixon v. Administrator ofGeneral Services, 433 U.S. 425,443 (1977) (congressional enactment that “disrupts the proper balance between the coordinate branches” may violate the separation of powers).Congressional oversight of the process by which the Executive Branch responds to congressional oversight inquiries would create a detrimental dynamic that is quite similar to what would occur in litigation if lawyers had to disclose to adversaries their deliberations about the case, and specifically about how to respond to their adversaries’ discovery requests. As the Supreme Court recognized in establishing the attorney work product doctrine, “it is essential that a lawyer work with a certain degree of privacy, free from unnecessary intrusion by opposing parties and their counsel.” Hickman v. Taylor, 329 U.S. 495, 510-11 (1947). Were attorney work product “open to opposing counsel on mere demand,” the Court explained, “[i]nefficiency, unfairness and sharp practices would inevitably develop in the giving of legal advice and in the preparation of cases for trial … , [a]nd the interests of the clients and the cause of justice would be poorly served.” !d. at 511.

Similarly, in the oversight context, as the Department recognized in the prior administration, a congressional power to request information from the Executive Branch and then review the ensuing Executive Branch discussions regarding how to respond to that request would chill the candor of those Executive Branch discussions and “introduce a significantly unfair imbalance to the oversight process.” Letter for John Conyers, Jr., Chairman, Committee on the Judiciary, U.S. House ofRepresentatives, and Linda T. Sanchez, Chairwoman, Subcommittee on Commercial and Administrative Law, Committee on the Judiciary, U.S. House of Representatives, from Richard A. Bertling, Acting Assistant Attorney General, Office of Legislative Affairs at 3 (Mar. 26, 2007). Such congressional power would disserve both Branches and the oversight process itself, which involves two co-equal branches of government and, like litigation, often is, and needs to be, adversarial. We recognize that it is essential to Congress’s ability to interact independently and effectively with the Executive Branch that the confidentiality of internal deliberations among Members of Congress and their staffs be

protected against incursions by the Executive Branch. See Gravel v. United States, 408 U.S. 606, 616 (1972) (“The Speech or Debate Clause was designed to assure a co-equal branch of the government wide freedom of speech, debate, and deliberation without intimidation or threats from the Executive Branch.”). It is likewise essential to the Executive Branch’s ability to respond independently and effectively to matters under congressional review that the confidentiality of internal Executive Branch deliberations be protected against incursions by Congress.Moreover, there is an additional, particularized separation of powers concern here because the Committee’s inquiry into Fast and Furious has sought information about ongoing criminal investigations and prosecutions. Such information would itself be protected by executive privilege, see, e.g., Assertion of Executive Privilege in Response to Congressional Demands for Law Enforcement Files, 6 Op. O.L.C. 31,32 (1982) (opinion of Attorney General William French Smith) (“[I]t has been the policy of the Executive Branch throughout this Nation’s history generally to decline to provide committees of Congress with access to or copies of law enforcement files except in the most extraordinary circumstances.”). Consequently, the Department’s deliberations about how to respond to these congressional inquiries involved discussion of how to ensure that critical ongoing law enforcement actions are not compromised and that law enforcement decisionmaking is not tainted by even the appearance of political influence. See, e.g., id. at 33 (noting “substantial danger that congressional pressures will influence the course ofthe investigation … [and] potential damage to proper law enforcement which would be caused by the revelation of sensitive techniques, methods, or strategy”) (quotation marks omitted). Maintaining the confidentiality of such candid internal discussions helps preserve the independence, integrity, and effectiveness of the Department’s law enforcement efforts.

III.

A congressional committee “may overcome an assertion of executive privilege only if it establishes that the subpoenaed documents are ‘demonstrably critical to the responsible fulfillment of the Committee’s functions.”‘ Special Counsel Assertion at 5-6 (quoting Senate Select Comm. on Presidential Campaign Activities v. Nixon, 498 F.2d 725,731 (D.C. Cir. 1974) (en bane) (emphasis added)); see also, e.g., US. Attorneys Assertion at 2 (same); Clemency Assertion, 23 Op. O.L.C. at 2 (same); Nixon, 418 U.S. at 707 (“[I]t is necessary to resolve those competing interests in a manner that preserves the essential functions of each branch.”). “Those functions must be in furtherance of Congress’s legitimate legislative responsibilities,” Special Counsel Assertion at 5 (emphasis added), for “[c]ongressional oversight of Executive Branch actions is justifiable only as a means of facilitating the legislative task of enacting, amending, or repealing laws.” 1981 Assertion, 5 Op. O.L.C. at 30-31. See also, e.g., Special Counsel Assertion at 5; US. Attorneys Assertion at 2-3; McGrain v. Daugherty, 273 U.S. 135, 176 (1927) (congressional oversight power may be used only to “obtain information in aid of the legislative function”); Eastland v. US. Servicemen’s Fund, 421 U.S. 491, 504 n.15 (1975) (“The subject of any [congressional] inquiry always must be one on which legislation could be had.”) (quotation marks omitted).

A.

The Committee has not satisfied the “demonstrably critical” standard with respect to the documents at issue. The Committee has said that it needs the post-February 4 documents “related to the Department’s response to Congress” concerning Fast and Furious in order to “examine the Department’s mismanagement of its response to Operation Fast and Furious.” Chairman’s Letter at 1-2. More specifically, the Committee has explained in the report that it is scheduled to consider at its June 20 contempt meeting that it needs these documents so that it can “understand what the Department knew about Fast and Furious, including when and how it discovered its February 4 letter was false, and the Department’s efforts to conceal that information from Congress and the public.” Comm. on Oversight and Gov’t Reform, U.S. House ofRepresentatives, Report at 33 (June 15, 2012). House leaders have similarly communicated that the driving concern behind the Committee’s scheduled contempt vote is to determine whether Department leaders attempted to “mislead or misinform Congress” in response to congressional inquiries into Fast and Furious. See Letter for Eric H. Holder, Jr., Attorney General, from John A. Boehner, Speaker, U.S. House of Representatives, et al. at 1 (May 18, 2012) (“Speaker’s Letter”).

At the threshold, it is not evident that the Committee’s asserted need to review the management of the Department’s response to congressional inquiries furthers a legislative function of Congress. See WHCO Documents Assertion, 20 Op. O.L.C. at 4 (noting the question of “the extent of Congress’s authority to conduct oversight ofthe executive branch’s response to oversight … must be viewed as unresolved as a matter oflaw in light of the requirement that there be a nexus to Congress’s legislative authority”). In any event, the purported connection between the congressional interest cited and the documents at issue is now highly attenuated as a result ofthe Department’s extraordinary efforts to accommodate the Committee’s interest in this regard. Through these efforts, the Department has amply fulfilled its constitutional “obligation… to make a principled effort to acknowledge, and if possible to meet, the [Committee's] legitimate needs.” 1981 Assertion, 5 Op. O.L.C. at 31; see also, e.g. , United States v. AT&T, 567 F.2d 121, 127, 130 (D.C. Cir. 1977) (“[E]ach branch should take cognizance of an implicit constitutional mandate to seek optimal accommodation through a realistic evaluation of the needs of the conflicting branches in the particular fact situation…. Negotiation between the two branches should thus be viewed as a dynamic process affirmatively furthering the constitutional scheme.”).

Specifically, the Department has already shared with the Committee over 1300 pages of documents concerning the drafting of the February 4 Letter, in acknowledgment that the February 4 Letter contained inaccurate information. In addition, numerous Department officials and employees, including the Attorney General, have provided testimony and other statements concerning both the conduct of Fast and Furious and the Department’s preparation and withdrawal of the February 4 Letter. This substantial record shows that the inaccuracies in the February 4 Letter were the inadvertent product of the fact that, at the time they were preparing that letter, neither Department leaders nor the heads of relevant Department components on whom Department leaders reasonably relied for information knew the correct facts about the tactics used in Fast and Furious. Department leaders first learned that flawed tactics may have been used in Fast and Furious when public allegations about such tactics surfaced in early 2011, after such tactics had been discontinued. But Department leaders were mistakenly assured by the heads of relevant Department components that those allegations were false. As the Department collected and reviewed documents to provide to the Committee during the months after submitting the February 4 Letter, however, Department leaders came to understand that Fast and Furious was in fact fundamentally flawed and that the February 4 Letter may have been inaccurate. While the Department was developing that understanding, Department officials made public statements and took other actions alerting the Committee to their increasing concern about the tactics actually used in Fast and Furious and the accuracy of the February 4 Letter. When the Department was confident that it had a sufficient understanding of the factual record, it formally withdrew the February 4 Letter. All of this demonstrates that the Department did not in any way intend to mislead the Committee.

The Department continued its extraordinary efforts at accommodating the Committee by recently offering to provide the Committee with a briefing, based on documents that the Committee could retain, explaining further how the Department’s understanding of the facts of Fast and Furious evolved during the post-February 4 period, as well as the process that led to the withdrawal of the February 4 Letter. The Department believes that this briefing, and the accompanying documents, would have fully addressed what the Committee described as its remaining concerns related to the February 4 Letter and the good faith of the Department in responding to the Committee’s investigation. The Committee, however, has not accepted this offer of accommodation.

Finally, the Committee’s asserted need for post-February 4 documents is further diminished by the Inspector General’s ongoing investigation of Fast and Furious, which was undertaken at my request. As an Executive Branch official, the Inspector General may obtain access to documents that are privileged from disclosure to Congress. The existence of this investigation belies any suspicion that the Department is attempting to conceal important facts concerning Fast and Furious from the Committee. Moreover, in light of the Inspector General’s investigation, congressional oversight is not the only means by which the management of the Department’s response to Fast and Furious may be scrutinized.

In brief, the Committee received all documents that involved the Department’s preparation of the February 4 Letter. The Committee’s legitimate interest in obtaining documents created after the February 4 Letter is highly attenuated and has been fully accommodated by the Department. The Committee lacks any “demonstrably critical” need for further access to the Department’s deliberations to address concerns arising out of the February 4 Letter.

B.

The Department’s accommodations have concerned only a subset of the topics addressed in the withheld post-February 4 documents. The documents and information provided or offered to the Committee address primarily the evolution of the Department’s understanding of the facts of Fast and Furious and the process that led to the withdrawal ofthe February 4 Letter. Most of the withheld post-February 4 documents, however, relate to other aspects of the Department’s response to congressional and related media inquiries, such as procedures or strategies for responding to the Committee’s requests for documents and other information. The Committee has not articulated any particularized interest in or need for documents relating to such topics, let alone a need that would further a legislative function.

“Broad, generalized assertions that the requested materials are of public import are simply insufficient under the ‘demonstrably critical’ standard.” US. Attorneys Assertion at 3; see also, e.g., Congressional Requests Opinion, 13 Op. O.L.C. at 160 (“‘A specific, articulated need for information will weigh substantially more heavily in the constitutional balancing than a generalized interest in obtaining information.”‘) (quoting 1981 Assertion, 5 Op. O.L.C. at 30)). Moreover, “Congress’s legislative function does not imply a freestanding authority to gather information for the sole purpose of informing ‘the American people.’” Special Counsel Assertion at 6. The “only informing function” constitutionally vested in Congress “‘is that of informing itself about subjects susceptible to legislation, not that of informing the public.”‘ !d. (quoting Miller v. Transamerican Press, Inc., 709 F.2d 524, 531 (9th Cir. 1983)). In the absence of any particularized legitimate need, the Committee’s interest in obtaining additional post¬ February 4 documents cannot overcome the substantial and important separation of powers and Executive Branch confidentiality concerns raised by its demand.

* * * *

In sum, when I balance the Committee’s asserted need for the documents at issue against the Executive Branch’s strong interest in protecting the confidentiality of internal documents generated in the course of responding to congressional and related media inquiries and the separation of powers concerns raised by a congressional demand for such material, I conclude that the Committee has not established that the privileged documents are demonstrably critical to the responsible fulfillment of the Committee’s legitimate legislative functions.

IV.

For the reasons set forth above, I have concluded that you may properly assert executive privilege over the documents at issue, and I respectfully request that you do so.

Sincerely,

Eric H. Holder, Jr. Attorney General

The President's Response

November 2011 - Murdered Agent Brian Terry's Family Speaks Out on Holder and Fast & Furious

February 2012 - Brian Terry's Family Sued ATF

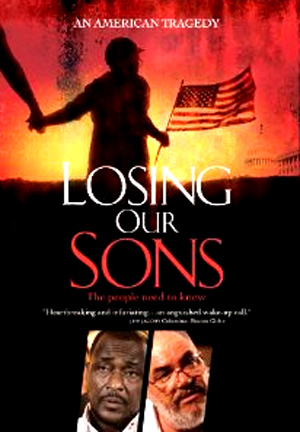

A DVD on the real tale of two fathers losing their sons to radical Islam that the U.S. Governement refuses to address . . . one son the shooter, the other the victim. Losing Our Sons Trailer

Addendum

A Very Interesting Comment No One is Talking About!

"I am thinking that Eric Holder and Obama are covering up Elena Kagan's involvement in the Justice Dept "Gun Walking" debacle...18 months ago would be March 2011. She was Obama's Solicitor General for 15 months. The Left would loose a seat on the Supreme Court...no small loss...Fast and Furious was obviously setup and signed off on months before. If her name is found on any documents that would be explosive.

Do some digging and send info and ideas out to people like Lou Dobbs and Congressmen Issa and Gowdy and the Daily Caller . . . etc. NOBODY is thinking of who else stands to loose a lot. Here are some timelines for starters:" - Dr. Ellen Rudolph

Obama picks Elena Kagan for Supreme Court

DOJ Memo: Solicitor General Kagan ‘Substantially Participated’ in Obamacare-Related Case

Obama picks Solicitor General Elena Kagan for Supreme Court

Judiciary Committee Launches Probe of Kagan’s Involvement in Obamacare

Showdown on Arizona immigration law goes to Supreme Court

Chief Justice's Report Ducks Ethics Scandals

Elena Kagan Lied to Supreme Court in 9/11 Case

President Obama to Senate: Act fast

Justice Kagan recuses self as Supreme Court takes up Arizona immigration law

Again, thanks to Dr. Ellen Rudolph for this interesting contribution

Watch your backs, Harvard grads. George is watching!

President Obama’s Fast and Furious Scandal Grows

Thank you for considering to pass along these e-mails. Did you miss one of our e-mails?

HTML E-mail Content from Freedom is Knowledge

OnfreedomisknowledgeOnfreedomisknowledgeOnfreedomisknowledgeOnfreedomisknowledgeOnfreedomisknowledgeOnfreedomisknowledgeOnfreedomisknowledgeOnfreedomisknowledge

Obama's 1990 article would foreshadow his presidency - “We’re Going To Reshape Mean-Spirited Selfish America.”

Click here for a printable page of Barack Obama's 1990 Newspaper Article

| Fascism in America | It Doesn't Matter?! | 50 Reasons Marxists for Obama | What Privacy? | America Facing Evil |

We live in historic Biblical Times

It is no measure of health to be well-adjusted to a profoundly sick society - J. Krishnamurti

Listen to The Jimmy Z Show on the Internet - The right wing from the left coast!

__________________________

HOW TO SEARCH FOR CONTENT ON OUR CONSERVATIVE PORTAL

Freedom is Knowledge content can be easily word-searched using the Atomz Search Engine at the top of its homepage along with Windows "Ctrl + F" FIND feature used for locating search words on any pages brought up in an Atomz search. Once you review the HTML pages brought up by the Atomz Search Engine, click on a page to brought up. It will appear in your browser. Hold the "Ctrl +F" keys and a box will appear in the upper left top of the page. Type in the exact same word(s) you used in the original search. The word you typed in will immediately be highlighted where it is located on the page. Click the Next Button to see if it appears anywhere else on the page, or back up using the Previous Button.

Try it now.

Go to Atomz Search Engine at the top of the Freedom is Knowledge homepage and type in Darth Tader. Click on the gray bar. A page will come up with two selections to the words you typed in. Click on the URL of either one. When the page loads hit the "Ctrl +F" keys together. Type in (or paste in) Darth Tader into the empty box at the upper left top of the page. You will be immediately taken to where the words Darth Tader appears. Enjoy the Grocery Store Wars video.

Webmaster

Western North Carolina

www.freedomisknowledge.com

Background photo source: President George Washington

![Reporter for Newsbuster writes, " 'Time' ran the photo without comment. I haven't seen coverage of this anywhere else in the MSM [mainstream media.] Perhaps some enterprising reporter can ask the Illinois senator about his decision to spurn this American tradition." Download video to watch event.](../../troop/obamadoesnthonornationalant.jpg)